What is an independent bottler? How it works, 'teaspooning' and more

What is an independent bottler? We spoke to Simon McGoram to learn more, what teaspooning is, and what That Boutique-y Whisky Company's new Australian series is about.

What is an independent bottler? When it comes to the Scotch whisky world, you’ve got the releases form the big name distilleries, you’ve got releases from smaller, independent distilleries, and then you have the kind of odd world of independent bottlings.

There really is a lot of independently bottled whisky out there — so much that The Elysian Whisky Bar in Melbourne (which you can read about here) stocks their entire bar with the stuff.

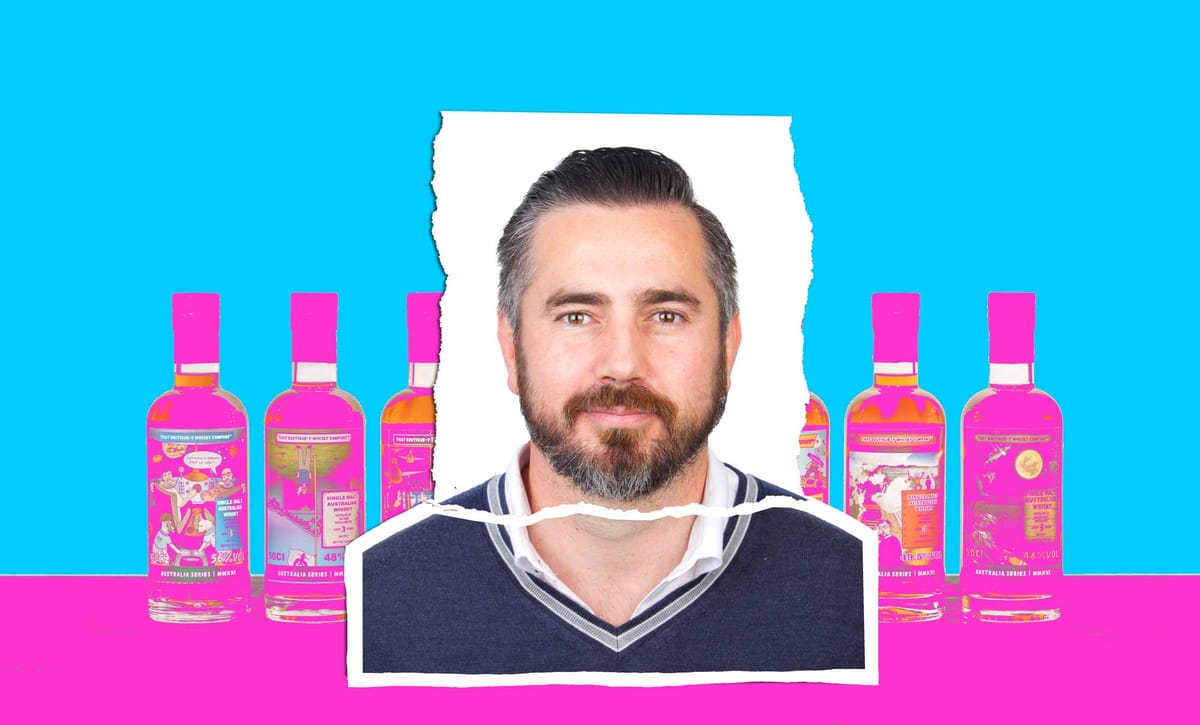

That Boutique-y Whisky Company is one such independent bottler, and they’ve been making some noise in recent days thanks to the release of an Australian series of whiskies. So we thought we’d chat to Simon McGoram — one of Australia’s big whisky brains who works with Boutique-y — to get an idea of what it is that an independent bottler does, how they differ from mainstream releases, and about the peculiar idea of ‘teaspooning’.

Simon, just what is an independent bottler?

An independent bottler is something that’s been around quite a long time, particularly in the Scotch whisky industry. I think we forget that the majority of Scotch whisky is still blended, right? It’s an offshoot of that long history of blending whisky, Scotch in particular.

We are fairly modern in terms of independent bottling. That Boutique-y Whisky Company has only been around since 2012, and we’re competing against the likes of Berry Bros & Rudd, which trace their origins back to the 17th century; William Caidenhead, and Gordon & MacPhail, were both founded in the 19th century, even something like the Scotch Malt Whisky Society — which is one of the new kids on the block — has been around since the 1980s.

So you’re babies.

We’re babies in comparison. We’ve just been very prolific since we started back in 2012.

Why do these independent bottlings exist?

I guess you reach a level of nerdiness in your whisky drinking life, where you just want to try something else apart form the official bottlings. Whilst the likes of Pernod Ricard and William Grant & Sons produce amazing liquids, and their offical bottlings are great, people are always striving to try something a bit new.

The idea of craft and small batch is nothing new in the spirits industry, and people still desire that in whisky as well. Independent bottling offers you the chance to try a side of that distillery you might not have tried before, because often they will be single casks or the marriage of one or two casks — not necessarily a marriage of dozens.

OK, so how are independent bottlers able to get their hands on these whiskies? Don’t the distilleries want to keep their whisky to themselves?

This is a bit of a common misconception, that independent bottlers actually buy straight off the distillers. When we’re working with new world whiskies, like with our Australian series, we will definitely work directly with distillers and buy directly from the distillery. But in the Scotch whisky industry there’s a huge secondary market of whisky brokers, of people buying, selling and trading casks. And this is due to the need for this to fulfil the requirements of blenders.

In Scotch in particular there’s this huge industry of trading casks, and that’s where we get the majority of our liquid from.

We also get liquid from private collectors as well, it might have been somebody who worked at a distillery for decades that happened to get two of their own barrels and they’ve been sitting on them and want to offload them. People will also invest in schemes to help distilleries get off the ground, we’ve seen that happen in Australia, and then at some point they’ll want to sell their cask that they have invested in.

So there’s three main avenues for a bottler: from brokers is the main one, particularly for Scotch whisky; from private collectors; and then finally from the distilleries themselves.

You’ve got an Australian series of whiskies coming out in April, is that something that has been done before with Australian whisky?

We did an Overeem bottling back in 2016, and there’s been a few people [to do it] — I think SMWS have done one, I think Berry Bros & Rudd have done one, so there have been independent bottlers look at Australia but no-one’s really done a comprehensive series of eight different distilleries so you’ve got a real cross-section of what is happening in the Australian whisky industry right now.

So we deliberately designed it like that: we’ve got two distilleries in New South Wales, two in Victoria, two from South Australia and two from Tasmania.

Sorry WA. But we don’t know how long WA will be part of Australia, right?

A lot of Australian whiskies have younger age statements on them than their Scotch whisky counterparts — can you tell us why that is?

Yeah. Obviously climate does have a big impact on how whisky matures, and I think that the Australian industry has really understood that. It has had enough time now to understand that they can’t necessarily be releasing 10 or 12 year old whiskies. Also, some of these distilleries haven’t been around that long.

Quite a selection of these whiskies we have in the series have been matured in smaller casks, and haven’t been matured for as long but that’s because they don’t necessarily need that long to reach maturity.

And they’re not necessarily trying to emulate Scotch whisky. This series, I think what it shows is that Australian whisky is its own beast, and that Australian whisky is going to be a force to be reckoned with in the future.

Back when people could fly overseas, you got around Asia Pacific quite a bit — is that something that people overseas understand? Because so many people still tend to think that age is equal to quality.

I think there’s still some work to be done there, for sure. I think particularly in the Asia Pacific region it’s still very Scotch-centric. But where the Australian series is selling is in the UK and Europe, and they understand it — they are excited about new world whiskies and there’s a similar craft whisky revolution happening in Europe where there are distilleries in Sweden and Germany and in Finland, France, producing amazing liquid that may only be five years old but it’s bloody delicious. And that’s what matters right?

The US gets it as well. They are used to producing younger whiskies, they don’t need a big age statement for it to have — you know, outside of the Pappy Van Winkle drinkers — they don’t need a big age statement to make that whisky valuable.

There’s a bit of a coded language around the products from some Scotch distilleries when it comes to independent bottlings, isn’t there? Can you tell us about that?

This does happen quite a lot, it’s quite particularly to independent bottlers for Scotch whisky. This mostly refers to ‘teaspooning’.

This happened because of the 80s. In the 1980s there was a huge crash in the demand for whisky. Australia was one of the top five producers of whisky in the world up until the 1980s, but all of the distilleries were shut down because they were owned by British concerns.

Distillers Company Ltd, which later became Diageo, owned Corio for instance. And if you were a bit of a cynic, you might say that they shut it down to export more Scotch to Australia, because the Scotch industry was really struggling.

All of a sudden, during the 1980s — because it was all about blends, blends were king — people started marketing single malt whisky because they needed a way to sell all these casks of whisky that the blenders no longer needed.

People were almost giving away casks, they were dirt cheap, so you had a lot of what is called armchair bottlers pop up. Anyone could buy a cask, bottle it themselves and start selling it.

At this stage people started getting a little bit concerned at what was being put out there. Understandably they wanted to protect their distillery IP.

The guys who were real leaders of this were William Grant & Sons, and if you speak to any of the guys there they will swear that they never ever sell [casks of] Balvenie or Ailsa Bay or Glenfiddich — and technically they’re right. They don’t because they teaspoon it — if you add a dash of a single malt into another single malt, now it technically becomes a blended malt so you can’t use the name of that single malt.

A great example is if you take a dash of Balvenie and put it into a Glenfiddich, it becomes a Warhead; if you do the reverse, it becomes a Burnside. The other famous one is Glenmorangie. If you put a dash of Glen Moray into Glenmorangie it becomes a Westport. There’s another one — a Balvenie into an Ailsa Bay becomes a Dalrymple. A code name for Laphroaig, whether it’s teaspooned or not, is a Williamson.

There’s all these trade names in the industry for these casks, so you are technically getting a single malt but you can’t call it a single malt.

So if you get a Burnside, you’re pretty much drinking a Balvenie — you just can’t use the brand name.

The Boutique-y Whisky Company Australian series goes live in April, and it’s extremely limited stock, according to McGoram. The trade can get their hands on it via Proof & Company, and you can find it in good bottle shops like The Oak Barrel in Sydney, Old Barrel House, and Nick’s Wine Merchants in Melbourne.