How does a bartender see the world? Lucy Pallett-Jones explores that with In The Weeds

Lucy Pallett-Jones is both photographer and hospo professional; In The Weeds takes place Sunday 1 May.

Do bartenders see the world differently to civilians? With the late nights, long hours and weekends spent hosting the rest of humanity — serving them at their best and worst — hospitality offers a unique perspective on the world.

Lucy Pallett-Jones has been working in bars ever “since I was legal,” she says, and as both hospitality professional and photographer, she’s got a unique view on the bar world. It’s also the subject of her latest exhibition, In The Weeds, which takes place at Sydney cocktail bar Re on Sunday 1 May.

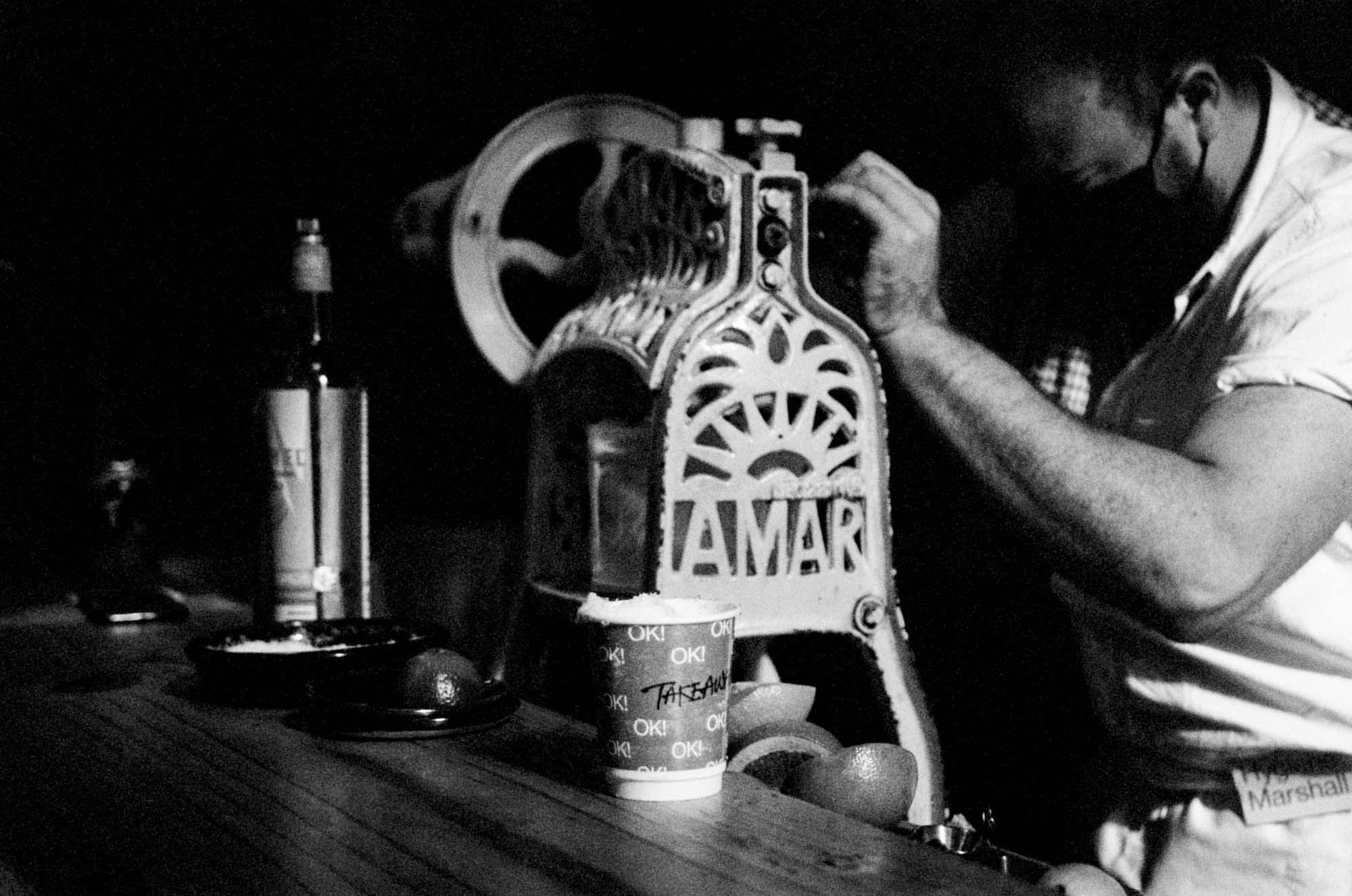

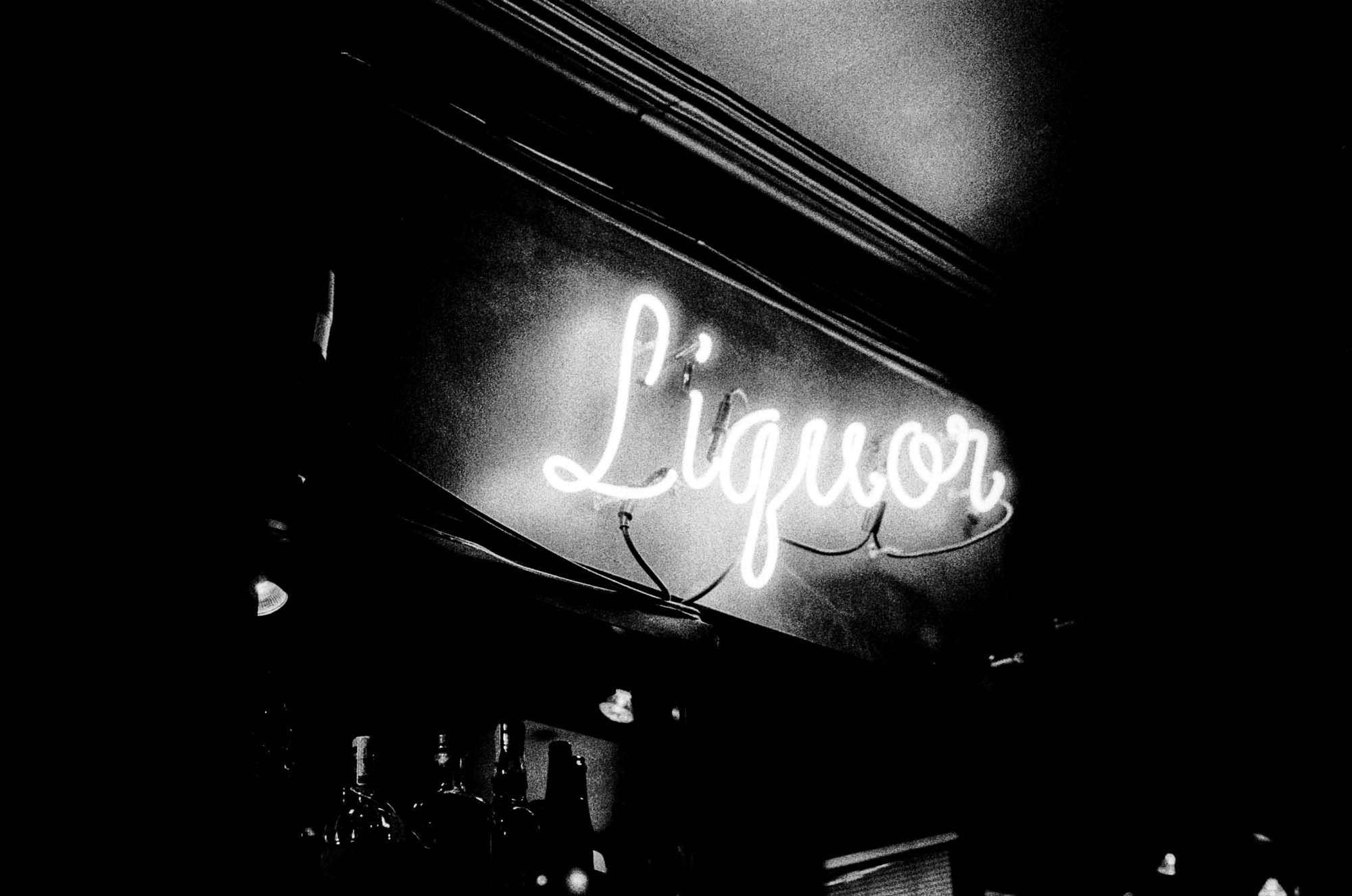

Her images are grainy, black and white, romantic visions of the bar world; below, she tells us what the attraction of the bar is for her as a photographer, why she shoots only on film, and why she’s putting together this exhibition at Re.

What’s the attraction of the bar world for you as a photographer?

I’ve been working in the booze industry since I was legal. Bars are my home, and they’re the only place I’ve ever been allowed to be truly myself, and loved for it. In every other job, I was too much: too loud, too blunt, too aggressive, too forward. The great bartenders I know would quit if they ever made someone feel like that. The best people in our industry bleed to make you feel good. They make time stand still for me, and it’s in that vortex that I take photographs.

What’s behind your choice to use film rather than digital? What does that do for your subject?

This is my favourite question. You can feel a film photograph. The grain, the tone and the texture transcend what we see: you can hear the moment it was captured. In my work, that sound is the hum of service. You can give an object life with this hum. That in particular is crucial in bars, because the very surfaces we touch and the shape of every object vibrate with energy.

When you’re shooting film, there’s no going back to check if it looks right. You don’t get to do that until much later, when the film is developed. So you tend to absorb yourself in your environment. It enables you to have gonzo experiences and for them to be authentic. The process is organic, and people relax around you; you’re not stressed, so they’re not stressed, and you don’t have this massive camera between you that’s firing off a thousand frames a second.

The downside is that you do f*ck up a lot. I used to really struggle with this because there’s absolutely no hiding from it. But once I became comfortable with that part of the process, I found both myself and others enjoyed my work a lot more. People love no f*cks.

What are the challenges in putting on an exhibition in a bar compared to a gallery?

Galleries are set up to exhibit art. Bars are not. I would illustrate the event as an ‘installation,’ so if you consider every element an exhibition requires (the art and lighting rigs as a starter) and the logistics of installing them in 12 hours, you may find your palms as sweaty as mine. It’s a pretty baller move though. I can’t wait to get on the scissor lift.

What is it you like about Re and why did you choose to have the exhibition there?

Firstly, the venue is aesthetically fabulous. Levels, textures, tones; it’s visually very dynamic, which makes it a hell of a challenge to curate within. If you haven’t been to Re before, it’s this strange harmony of old bones and the future. The building is ancient but the build within it is recycled. The bar top feels beautiful.

Secondly, I wanted to work with Matt [Whiley] and Evan [Stroeve]. They’re weapons. Operating an event in their sphere has shifted me into a gear I didn’t know I possessed. You get a lot done in that gear.

What do you hope people come away with having looked at your work?Recently I was at a lock-ins at Bar Rochford after the Intoxicating Beggars book tour. Gerald Diffey had us all glassy eyed with massive yarns about the industry. Through the dart smoke, three words came from his mouth which changed me:

“It’s worth it.”